Practice – introduction: Four Main Paths

In order to understand the spiritual practices outlined in this section, it is useful to have an overview of the main processes or “paths” (see One Goal, Different Paths). Some authorities list three, others add a fourth. Many thinkers claim that all paths are equally valid and effective and that the choice depends on individual inclination. Others suggest that all four paths are stepping stones along one spiritual path, each building progressively on the previous, more elementary disciplines. Either way, it is not that the different paths are tightly compartmentalised – each may contain elements of the others. Additionally, there may be higher and lower understandings of each path, as we explore below.

Karma-yoga (the yoga of selfless action)

Karma-yoga begins with the understanding that selfish action binds the soul. By giving up the fruits of action, one is relieved from the reactions to self-centred activities.This does not mean giving up the activity itself, for karma-yoga, on a lower level, recommends that all activities be linked to a greater cause. Karma-yoga specifically refers to sacrifices offered to various deities to attain material necessities in this life and the next, without accruing any reaction. On the highest level, karma-yoga means the unreserved dedication of all activities to serve the Supreme Lord. Karma-yogis tend to have a materially progressive attitude towards the world and their aim is often the heavenly planets.

Karma-yoga begins with the understanding that selfish action binds the soul. By giving up the fruits of action, one is relieved from the reactions to self-centred activities.This does not mean giving up the activity itself, for karma-yoga, on a lower level, recommends that all activities be linked to a greater cause. Karma-yoga specifically refers to sacrifices offered to various deities to attain material necessities in this life and the next, without accruing any reaction. On the highest level, karma-yoga means the unreserved dedication of all activities to serve the Supreme Lord. Karma-yogis tend to have a materially progressive attitude towards the world and their aim is often the heavenly planets.

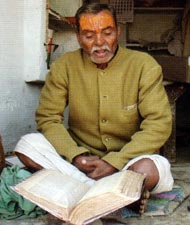

Jnana-yoga (philosophical research and wisdom)

Whereas karma-yoga usually involves bhukti, enjoying worldly pleasure, jnana-yoga promotes knowledge through seclusion, study, and sense abnegation. Activities and the necessities of life are minimised. Since the pursuit of wisdom and realisation is not simply an academic exercise, much emphasis is placed on becoming free from the sensual desires that delude the soul. Jnana is sometimes considered the antithesis of karma. Jnanayogis negate the world and usually aim at liberation (mukti or moksha).

Whereas karma-yoga usually involves bhukti, enjoying worldly pleasure, jnana-yoga promotes knowledge through seclusion, study, and sense abnegation. Activities and the necessities of life are minimised. Since the pursuit of wisdom and realisation is not simply an academic exercise, much emphasis is placed on becoming free from the sensual desires that delude the soul. Jnana is sometimes considered the antithesis of karma. Jnanayogis negate the world and usually aim at liberation (mukti or moksha).

Astanga/RajaYoga (physical exercises and meditation)

Asta means “eight” and anga means “part.” Astanga-yoga is a process divided into eight distinct and essential stages, based on the Yoga Sutras of the sage, Patanjali. It is explored succinctly in the Bhagavad-gita. Many modern practices of yoga are related. However, Patanjali’s system requires the observation of standards difficult for most contemporary practitioners. The sutras discuss superstates of consciousness and the obtainment of eight main types of mystic power, such as the ability to become “smaller than the smallest.” India is replete with tales of such feats, which are largely accepted as feasible. Nonetheless, Patanjali warns the yogi not to become enamoured of such mystic powers but to keep the mind fixed on leaving the material realm. The highest perfection is to focus on God within.

Asta means “eight” and anga means “part.” Astanga-yoga is a process divided into eight distinct and essential stages, based on the Yoga Sutras of the sage, Patanjali. It is explored succinctly in the Bhagavad-gita. Many modern practices of yoga are related. However, Patanjali’s system requires the observation of standards difficult for most contemporary practitioners. The sutras discuss superstates of consciousness and the obtainment of eight main types of mystic power, such as the ability to become “smaller than the smallest.” India is replete with tales of such feats, which are largely accepted as feasible. Nonetheless, Patanjali warns the yogi not to become enamoured of such mystic powers but to keep the mind fixed on leaving the material realm. The highest perfection is to focus on God within.

Bhakti-Yoga (the path of devotional service)

The popular path of bhakti is considered by many to be only a stepping-stone to what they consider the more difficult process of knowledge. Other groups consider bhakti to be higher than jnana, considering that “the heart rules the head.” Some consider all paths to be equal. Here as an act of devotion, a priest offers arti (see The Arti Ceremony) to the temple deities.

Bhakti (devotion) appears to be the path most recommended in the Gita. Krishna says that at the beginning, bhakti-yoga appears simple, but as it is perfected and as the practitioner matures, it combines all types of yoga. Within modern Hinduism, bhakti-yoga remains the predominant path towards spiritual fulfilment. It includes the external and symbolic worship of the murti, other practices such as pilgrimage and the sophisticated processes of inner development. It has often been condescendingly presented as suitable to those with emotional rather than intellectual dispositions, but thinkers such as Ramanuja, Madhva, and Vallabha have refuted such claims. Their theologies emphasise the importance of developing bhakti based on knowledge. They also stress the importance of grace in achieving such spiritual knowledge, often received via the guru, the mediator of God’s mercy. Though bhakti may involve approaching God for material benefit or liberation these are technically karma-yoga and jnana-yoga respectively. Bhakti-yoga is sometimes considered the synthesis and ultimate goal of karma and jnana. The goals of many bhakti schools transcend both bhukti (enjoyment) and mukti (liberation) and aim at pure, selfless service to a personal God.

Personal Reflection

- Are these paths confined to Hinduism or are they also found in other religions? If so, in what ways?

- Ask yourself: “What do I know about yoga as practiced in the West?” “What have I learned or how have my ideas changed?’

Scriptural Quotes

on karma-yoga

“Therefore, without being attached to the fruits of activities, one should act as a matter of duty, for by working without attachment one attains the Supreme.”

on jnana-yoga

“In this world, there is nothing so sublime and pure as spiritual knowledge, which is the mature fruit of all mysticism. One who has become accomplished in the practice of yoga enjoys this knowledge within himself in due course of time.”

on raja-yoga

“To practice astanga-yoga, one should go to a secluded place and should lay kusha grass on the ground and then cover it with a deerskin and a soft cloth. The seat should be neither too high nor too low and should be situated in a sacred place. The yogi should then sit on it very firmly and practice yoga to purify the heart by controlling his mind, senses and activities and fixing the mind on one point.”

on bhakti-yoga

“If one offers Me with love and devotion a leaf, a flower, fruit or water, I will accept it.”

Bhagavad-gita 3.19, 4.38, 6.11–12, 9.23

Glossary Terms

- Bhukti – worldly pleasure

- Mukti – another word for liberation